In summer 2024, I finally handed in my dissertation, after 5 years of research on privacy in human-computer interaction, as well as many more or less related topics. 331 pages, 11 incorporated research projects – lets be honest, nobody will ever read all of this. Thus, lets point out my main findings here in this article – hopefully you make it through this 🙂

Privacy-Preserving User-Quantification with Smartphone Sensing – What’s That?

Although that might seem different at first sight, people (maybe not all, but many) want User-Quantification – i.e., quantifying themselves through smartwatch sensors to measure their fitness and sports progress, or allowing their smartphone to use contextual data to adapt automatically to their situation and prompt intelligent suggestions when necessary. Doing this in a privacy-preserving way is essential; otherwise, people will start feeling bad or neglect service usage (a.k.a. uninstall apps again).

You may now ask: Is this really new and deserves a whole dissertation? Well, privacy is not new, of course. But with smartphones and intelligent applications, the situation has become different. Nowadays, ubiquitous technology is omnipresent (i.e., people take it with them everywhere: home, work, toilet, sleeping room, …) and constantly connected (i.e., they are, with most people, never off or offline). These two factors yield novel challenges that past privacy concepts are not tailored to.

But I promised takeaways instead of 331 pages of text, so let’s jump directly in!

#1 Agency Matters

„Agency, the abstract principle that autonomous beings, agents, are capable of acting by themselves.“ – Wikipedia

Smartphones make us lose our agency. Did you ever find yourself scrolling through Instagram Reels for half an hour without wanting to do so? That’s a loss of agency. Your smartphone, most often some content recommendation algorithm, decides for you what content you consume; you do not even decide on some topic or category anymore. Stopping this so-called Mobile Phone Rabbit Hole sometimes is difficult, although it theoretically would be just one easy tap to leave the app.

Consuming social media content is not necessarily bad; one can also strive for that as a means to relax. And here is the difference: In that case there is agency. In our research on the mobile phone rabbit hole we collected quantitative data on context of and behaviors in rabbit hole smartphone usage sessions. Furthermore we conducted a qualitative expert focus group. Our analyses showed that agency is what matters! If users are aware of and feel in control of their behavior, they are doing good. But if they rather feel steered by some algorithm, i.e., are not in agency anymore, their behaviors finally make them feel bad – leading to severe issues such as depression and other mental disorders which are nowadays fostered by „bad“ technology use.

This theme of agency is central in most privacy aspects – people want to be in control. Maybe they are not consciously aware of that, but offloading yourself to some system is rarely good.

#2 Technical Security Measures Hardly Mitigate Privacy Concerns

It is great if you build a system that is safe, processes most data locally on the user’s device, and handles all remaining data that is sent to a remote server anonymously. However, this does not automatically yield a great perception of privacy among your users. Users don’t know about your technical details and data processing procedures. And even if you tell them, they first need to trust you before they perceive your application as actually privacy-friendly.

System designers need to develop concepts that keep their users in the loop and convey the privacy-enhancing technologies they’ve incorporated.

#3 If you make your app’s data practices transparent to your users, they will honor it with rejection. Control is, what they want!

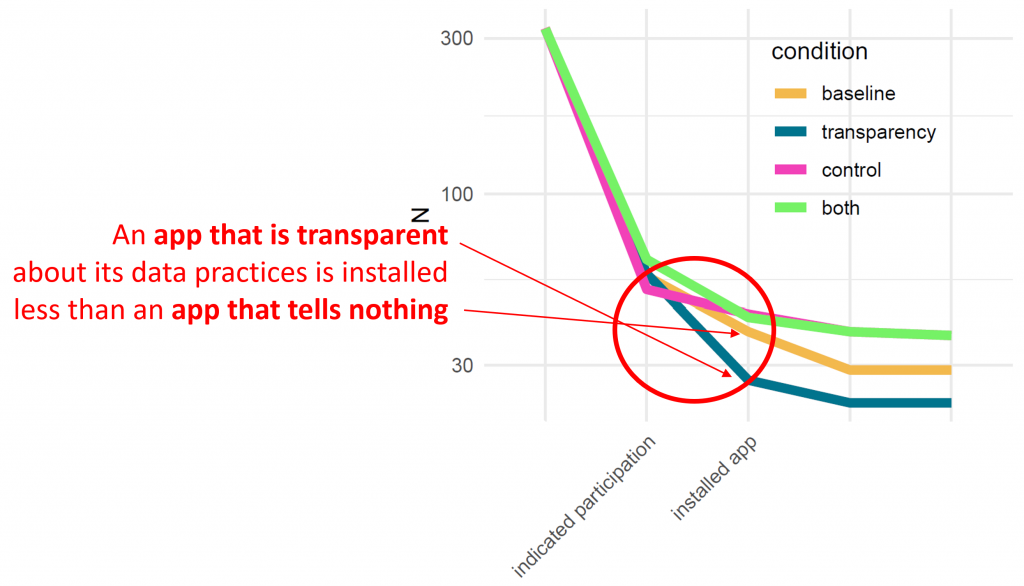

In a quantitative field study, we measured whether people install an app more or less frequently, depending on the offered privacy-enhancing features. I.e., we compared versions of an app with especially detailed Transparency features, one with fine-grained Control features, and one that implements both, with a baseline version that only incorporates the legal minimum.

The interesting finding: That version of the app that implemented a great privacy dashboard, thus being very transparent about what data it uses, was least appreciated! Users installed it significantly less frequently than all other versions – even less than the minimal baseline version.

At first sight surprising. On the second, it makes sense. As long as people are unaware of bad things happening, they don’t worry. But if you show them the plethora of data that a system uses without giving them any option to react, they start to be afraid. And helpless, powerless.

This effect is mitigated, and even surpassed, if you add Control features. The app version that gave users detailed control over what is logged at which point of time was appreciated most – and installed most often.

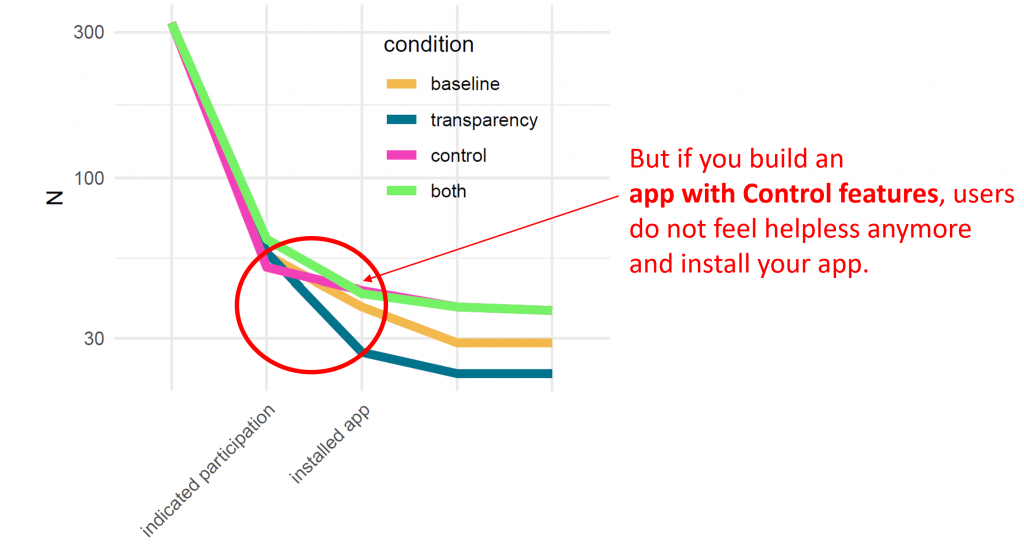

#4 The sole presence of Control makes the difference.

We also measured how our participants used the offered Control features. And interestingly, they rarely used them. Deducting initial tryouts directly after advertising these features, I could count the total number of data logging disabling actions with my fingers.

Thus, The presence of control makes the actual difference. The feeling and knowledge that one could change something anytime.

#5 We have to rethink opportune moments for privacy decisions.

Privacy interfaces act on the edge of user annoyance and warning fatigue. Simply spoken: Privacy is boring; users don’t want to spend time on that (with some exceptions. Indeed, the user population is quite polarized here).

And to make it worse, our privacy prompts often occur in moments when we really don’t want to spend time on privacy decisions. That means, in moments when we are pursuing some task. For example: I am buying a public transport ticket using a smartphone app. Location access is requested to determine my starting location; access to my wallet is requested to manage the payment. At that moment, I simply want to get my ticket fast. Thus, I don’t want to spend time considering different location granularities or limits and contextual access restrictions to my wallet. This entanglement of privacy decisions with concrete user actions makes sense and has advantages. Without this so-called contextualized privacy, we hardly understand the relationship between a data access request and its real-world relation and necessity. But it also comes with downsides.

We need to think about different ways to have contextualized privacy, i.e., users understanding the real-world context of a data request while prompting them in a more opportune moment, i.e., when they have time for that.

You want to read more? Then feel free to check out the full 331 pages of my dissertation, or follow me on Bluesky, LinkedIn, or Medium to be notified about future blog posts being released!